Part 2: How to ship a mobile app (aka The Submission Gauntlet).

I thought the hard part was behind me. Then Google hit me with 14 days of mandatory testing and essay questions that made me rethink everything.

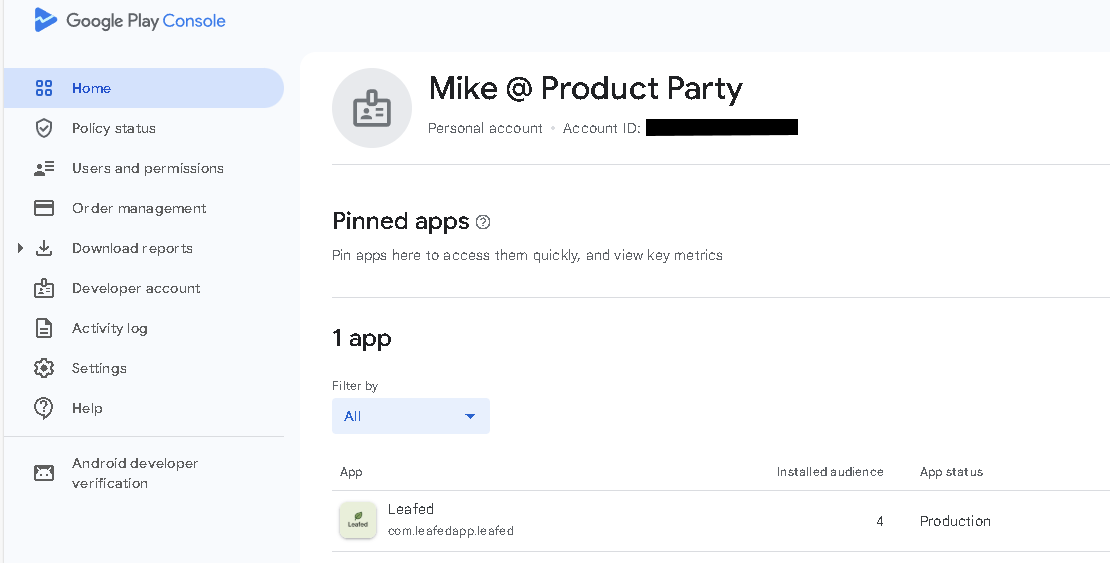

Last week, I walked through building Leafed, from discovering Cursor’s Agent “Plan” feature to cutting ambitious features like the Vivino-inspired bookshelf scanner. I was on day 13 of Google’s closed testing requirement, almost at the finish line.

Since then, I’ve submitted my production request to Google Play and started preparing for Apple’s App Store review.

This is what that journey looked like.

Nobody tells you about the 12-person, 14-day requirement.

You can’t just upload an app to the Play Store and launch. Google requires a mandatory closed testing phase before you can even apply for production access.

The specifics: At least 12 testers must opt in and actively engage with your app for a minimum of 14 consecutive days.

Not “download it once.” Actively engage. For two full weeks. Google tracks this. They really check.

I started recruiting. Friends who read books. Former colleagues. Family members. That person I met at a conference two years ago. “Hey, would you test my app for two weeks?”

People said yes. People downloaded it. Some people used it once and forgot. Others got busy. A few used it consistently. But coordinating 12 humans to actively use an app daily for 14 days straight?

That’s not a technical problem. That’s a people problem. And people problems are harder than code problems.

The $15 solution that saved two weeks.

After a week of watching my tester count hover around 8 actively engaged users, I did what any reasonable product person would do.

I searched for “Google Play closed testing service.”

Found one. They provide real testers who meet Google’s engagement requirements. Cost: $15.

Fifteen dollars.

I hesitated for about ten seconds. Then I paid.

This is one of those moments where you learn something about building products: Your time has value. Your momentum has value. Sometimes paying a small amount to solve a blocker is the smartest decision you can make.

The $15 wasn’t just buying testers. It was buying two weeks I would have spent recruiting, reminding, cajoling humans into daily app engagement.

Two weeks I could spend on literally anything else.

The testing period is actually preparation for the real test.

The 14-day requirement isn’t just a hoop to jump through. After those 14 days, Google doesn’t approve your app. They hit you with a production access application. Essay questions.

Real questions that require documented evidence:

How did you recruit testers? How easy was it?

Not “easy” or “hard.” They want context. Your target audience. Your recruitment strategy. What worked and what didn’t.

What features did testers engage with most? How does that compare to expected production behavior?

They want usage patterns. Evidence you actually watched how people used your app. Proof you understand the difference between test users and real users.

What feedback did you receive? What did you change based on that feedback?

Specific examples. Screenshots. Documentation of iterations. Proof you listened and improved.

How do you know your app is ready for production?

This isn’t “it works on my phone.” They want alignment with Android quality guidelines across four categories: Core Value, User Experience, Technical Quality, and Privacy & Security.

What value does this provide to users?

Not features. Value. The problem you solve. Why someone would choose your app over alternatives.

How many installs do you expect in year one?

Realistic projections with reasoning. Not inflated numbers. Not guesses.

I ended up writing what felt like a 3,000-word submission guide just to organize my answers. I used Cursor’s Agent “Plan” feature to help document my codebase and articulate how it met quality guidelines.

Screenshots of feedback. Documentation of every change I made during testing. Justification for why the dual chatbot implementations didn’t make the cut. Evidence that the barcode scanner (salvaged from the failed Vivino-inspired bookshelf scanner) was the feature people actually used.

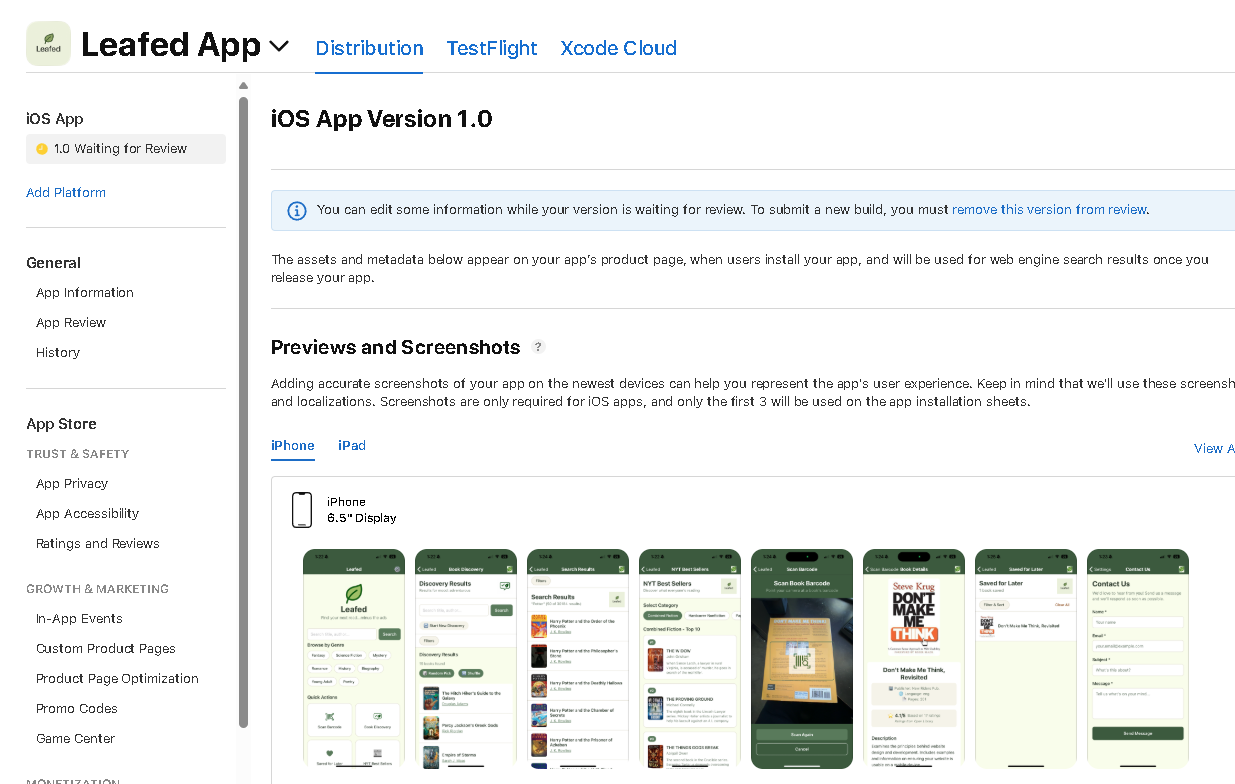

Apple takes a different approach, equally rigorous.

While preparing my Google submission, I was also getting ready for Apple through TestFlight.

TestFlight turned out to be one of my favorite tools in this entire process. Thanks to Expo handling the provisioning profiles and certificates (the things that usually make developers want to quit), I could deploy builds to myself instantly, test on my actual iPhone, and even use it to capture screenshots for the App Store listing. The workflow felt smoother than Google’s external testing coordination.

But don’t mistake “smoother workflow” for “easier approval.” Apple’s App Store review guidelines are notoriously thorough. The $99/year developer program fee signals something important: this is a curated platform with high standards.

The processes are similar but different:

Google focuses on testing evidence. They want proof you ran a legitimate closed test, collected feedback, and made improvements based on that feedback.

Apple focuses on guidelines compliance. They want assurance your app meets their design standards, privacy requirements, and user experience expectations.

Both want the same outcome: quality apps that won’t cause problems for users. They just verify it differently.

Why they make you jump through all these hoops.

Sitting there, writing detailed answers about my testing period for Google and preparing my Apple submission, I finally understood their logic.

The 14-day requirement forces you to actually use your app like a real user would. To collect real feedback. To make real product decisions about what matters.

By the time you’re answering these questions, you should have answers. Not because you’re good at writing essays, but because you lived through the process.

The technical barrier to building an app is lower than ever. Cursor, Expo, React Native, free APIs, open source components. All of that exists and works.

But the process barrier? That’s where Google and Apple make you prove you’re serious about shipping quality software to real people.

What this teaches about mobile products.

Building and shipping Leafed taught me things reading never would:

Distribution is completely different.

Web products live on URLs you control. Mobile products live behind gatekeepers with rules, review processes, and timelines you don’t control.

Feature planning requires discipline.

On web, you can ship fast and iterate. In mobile, every feature needs to justify its place before submission. You can’t easily roll back. You can’t A/B test post-launch without going through review again.

Compliance requirements are real. Privacy policies aren’t suggestions. Data safety forms aren’t optional. Target API levels have deadlines (Android 15 by August 2025, if you’re tracking).

Human factors are harder than code.

Getting the app built took days. Getting through testing and submission took weeks. Not because of technical problems. Because of process, people, and gatekeepers.

Knowing what NOT to ship is the real skill.

I built dual chatbot implementations and a Vivino-inspired bookshelf scanner. None of it made the cut. That’s not failure. That’s product judgment. The feature flag system let me build ambitious and cut intelligently.

Platform differences matter more than you think.

Even though I used React Native to share code, Google and Apple have fundamentally different philosophies about app quality and review. Understanding both makes you a better product person.

The ecosystem is richer than you realize.

Free APIs solve problems that used to cost thousands. Open source components save weeks of work. Tools like Expo abstract away platform complexity. The skill isn’t writing everything from scratch. It’s knowing what exists, finding it, and integrating it thoughtfully.

Tools are better than you think, but they’re not free.

As I mentioned last week, between developer accounts ($25 Google, $99 Apple), Cursor Pro ($20/month), Expo’s entry-level plan, and small service fees like that $15 testing solution, budget around $175 for the first year. The last 20% is learning what they can’t automate: compliance, testing coordination, and deciding what actually matters to users.

What you can apply tomorrow.

The principle applies whether you’re building an app or not:

Ask for the comprehensive plan before you start building.

Use Cursor’s Agent “Plan” feature. Whether it’s a product feature, a user flow, or a new system, get the full picture first. Not just the first step. The entire roadmap including deployment, testing, and what “done” actually means.

When you hit a blocker that money can solve? Consider paying for it. Sometimes $15 buys two weeks of momentum. Sometimes $20/month buys the ability to build in hours instead of days.

And when you’re deciding what to ship? Build ambitiously. Test honestly. Cut intelligently. The features you don’t ship teach you as much as the ones you do.

Waiting on two app stores.

Production request submitted to Google. Apple review preparation underway. Now I wait.

Maybe they’ll approve it. Maybe they’ll come back with questions. Maybe they’ll find something I missed.

Next week, I’ll share what happened and what this entire experience taught me about being a better product person. Because the real value wasn’t getting an app in the store. It was understanding the process in a way that changes how I think about mobile products, developer conversations, and what’s actually hard about shipping software.

Part 3 drops next Tuesday: What building taught me about product work, developer empathy, and why every product person should consider doing this once.

Until next week,

Want to connect? Send me a message on LinkedIn, Bluesky, Threads, or Instagram.

P.S. Planning your own app project? ClickUp is solid for organizing everything from feature checklists to submission requirements across multiple platforms.

I've been there, Mike, and I feel the pain...